“We have to work with the world,” Rouhani said Thursday, in what amounted to a plaintive, hour-long defense of his legacy at the nation’s central bank. To opponents who argue that Iran can succeed in isolation, ignoring the impact of foreign policy choices, he said: “Well, I don’t know how to do that.”

The response was swift. “The revolutionary youth know how. With the help of people anything is possible,” Mohammadbagher Ghalibaf, a former Tehran mayor, ex-Revolutionary Guard officer and three-time presidential candidate, wrote in a tweet.

Many conservatives interpret Khamenei’s ambiguous calls for a “resistance economy” to mean adjustment to sanctions through import substitution, coupled with reliance on China and Russia for investment and technology transfers.

The catch is that sanctions are only part of the problem in a country with sometimes difficult business conditions and a weak private sector, according to Cyrus Razzaghi, president of Ara Enterprise, a business consultancy in Tehran. Nor can China alone provide all the funds and technologies Iran requires to prosper.

“What’s needed is really massive structural reforms to make Iran more productive, with or without sanctions,” he said. “To be honest, I don’t see any manifesto or real policy to address these issues.”

The central bank said last week it was taking action to make it easier for private companies to export. Private companies are responsible for much of the $40 billion worth of non-oil goods Iran is still managing to send abroad annually, securing vital hard currency, the bank said.

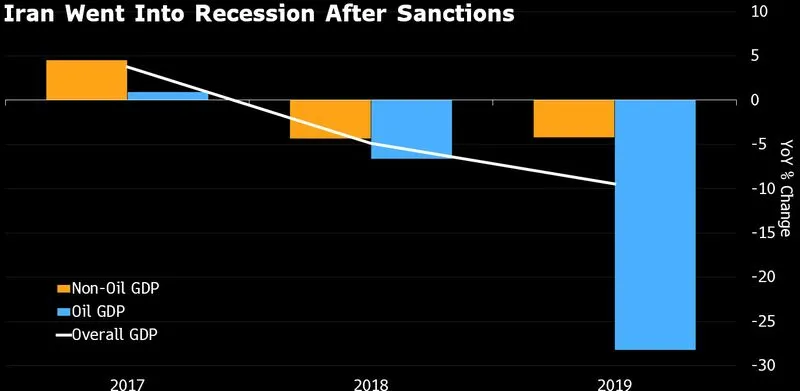

In many ways, the surprise is that Iran’s economy has survived as well as it has. The rial has stabilized after losing more than half its value when Trump pulled out of the nuclear deal in 2018. Middle class Iranians are scraping by.

Without dramatic external or internal relief for the economy, this resilience can’t last forever, Razzaghi said. He puts the limit somewhere in 2021. That economic fragility also means Iran “can’t afford further military escalation” with the U.S., Ziad Daoud of Bloomberg Economics said.

The economy has been badly damaged by the renewed sanctions, reimposed at a time when a lower oil price was in any case squeezing government revenue. During the last U.S.-led sanctions campaign against Iran, before the 2015 nuclear deal, former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad showered the population with handouts. That was made possible largely by an oil price around $120 per barrel. Oil has been closer to $60 per barrel for much of Rouhani’s term.